Review: Halloween (1978)

A look back at the first Halloween film from 1978, a John Carpenter classic.

Warning: Spoilers ahead!

John Carpenter’s Halloween exploits a fear of things we can’t see, of shapes that move under cover of darkness. That’s why escaped mental patient Michael Myers is referred to as “the shape”. He could conceivably take any form, any face (notice that the killer spends most of the film in the now famous Shatner mask). What we are talking about is Michael being a manifestation of evil, and how scary it is that we can’t easily detect this manifestation because it’s lurking beneath the surface of things that are supposed to be familiar and safe. Halloween takes place in small town Haddonfield, Illinois, which is a perfect backdrop – Carpenter uses it to peel away the layers of suburban utopia and show us the hidden dark side.

The film is a masterpiece of mood. It takes certain cues from Bob Clark’s seminal horror flick Black Christmas (most obvious is the killer-POV shots) and like Black Christmas, it registers low on the gore meter but high on atmosphere and suspense. Using the theme of Halloween as the setting, Carpenter is allowing us to remember our childhood fears. He remembers how cool it was to go trick-or-treating as a kid, to watch scary movies on the tube (The Thing From Another World is one of them – something Carpenter himself would remake a few years later), and he remembers what it was like to be a teenager, dealing with school, dating, and sometimes having to babysit, as poor Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) is asked to do. Then he scares us by putting that cult of childhood under threat. Halloween is so influential that while it is paying tribute to films before it (Hitchcock, for example – that’s why Donald Pleasance’s character is called Dr. Loomis), it is creating its own genre and trapping its actors in that genre at the same time. Friday the 13th and A Nightmare on Elm Street wouldn’t exist without Halloween, Curtis wouldn’t be referred to as the ultimate scream queen, and Donald Pleasance wouldn’t have forever been typecast as the unbalanced but determined shrink.

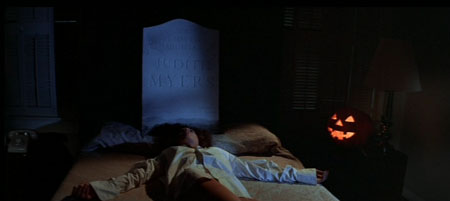

Asylum inmate Michael Myers escapes from the hospital and returns to his hometown where, years before when he was a boy, he put on a clown mask and brutally stabbed his sister to death. After years of attempted treatment, Dr. Loomis has decided that Myers is the embodiment of evil, and follows him back to Haddenfield. The first thing Myers does is dig up his sister, and then he proceeds to kill the straying teens in Laurie’s neck of the woods – mostly those teens who stray from the “path” (sex, usually). With the sex/death paradigm now established, selfless and well-behaved Laurie (with the sole exception of a scene with her smoking the reefer) will naturally become the “final girl”. (Interesting to note that Carpenter himself describes Laurie as attacking Myers with “sexually repressed energy”). And even though the killer ultimately disappears (evil can never really be eliminated) there is some catharsis in that our adult authority has finally wised up and realized that the kids were right all along (“That was the bogeyman,” exclaims Laurie, to which Loomis replies “As a matter of fact, it was.”). There are so many dissertations on Halloween out there, but one I have read that resonated with me was that Myers represented not so much evil as the entropy of an uncaring universe, and that as Laurie “comes of age” she must now deal with the new dangers in her wider world. Taking into account that the babysitters of the film, whether having sex or not, are still concerned with the welfare of the children they are supposed to be watching over, I think that these views are close to the mark. It’s too bad that all children must eventually grow up.

Of course, none of this would be so engaging if it wasn’t for Carpenter’s mastery of scope and music. The famous, creepy piano theme is all his, and there are shots in the movie (courtesy of Dean Cundey) that make brilliant use of foreground information along with some interesting Steadicam movement. Many scenes in it are iconic – I am particularly thinking of the scene where Michael pins a victim to the wall with a knife, then tilts his head to the side, studying his handiwork. He then strangles the victim’s girlfriend with a phone cord while wearing the guy’s glasses over a white sheet. There’s something so strange and giallo-like about it. Thirty years after its debut, I find Halloween still superior to almost anything in today’s horror cinema. (I watch it every Halloween as ritual). It’s amazing that a movie with a simple storyline, restrained gore, and modest budget can communicate so much and with elegance. This is a landmark film.

– Bill G